Architecture: The Monastery of the Sinai, its Founders and the Sacristy Quarters

About the construction of one of the oldest fortified monasteries from the 4th Century CE

Mount Sinai monastery is, without a doubt, one of the oldest fortified communal monasteries, boasting a continuous presence and evolution from the sixth century to the present. The construction of both its well-preserved walls and of the main church of the monastery is attributed by in situ inscriptions and written sources to the emperor Justinian. Some two centuries before this the greater area around the Mountain of Moses had already become a refuge for hermits.

Pilgrim Egeria, who had visited the peninsula probably around 383-384, reported that the hermits who lived close to the shrine of the Biblical Burning Bush had a beautiful garden with a well, many cells, and a church, all of which were later enclosed within the fortified courtyard of the Sinai Monastery. The only surviving structure, from these initial free-standing buildings, is a square tower, to which the monks retreated during raids. Sinai tradition, which attributes its construction to Saint Helen or at least to the age of her pilgrimage to Palestine (around 326), had preserved a record of its exact location within the Monastery to our day. This must also be the same tower mentioned in the Report of Monk Ammonios, who links it to the Forty Martyrs of Sinai, around the year 373.

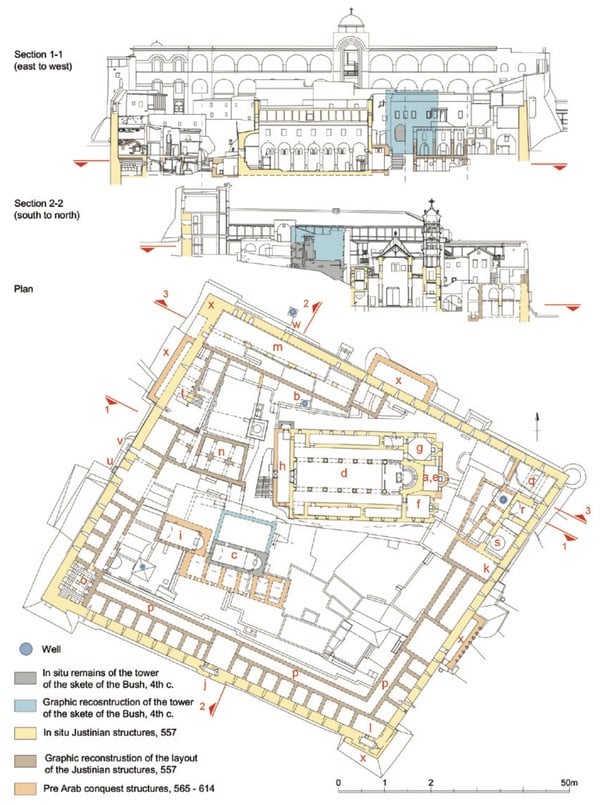

Based on structural details as well as data derived from the subsequent, but still dependable, account of the Patriarch of Alexandria Eutychios (933-944), modern research attests that the first small church of the Theotokos, the so-called kyriakon of the hermits, was located within this fourth century tower, in the space now housing the chapel of the Dormition of the Theotokos(fig.27). The maximum dimensions of Justinian’s fortified enclosure were about 76 x 90 meters. It was erected at the east end of the “Valley of the Monastery” (Wadi el Deir) (fig. 28).

The location of this enclosure, imposed by the pre-existing shrine and the tower, was rather unfavorable in terms of placement and security. The walls, whose thickness varied from 1.80 to 2.20 meters, still retain in many places the original battlements and parapet. In place of towers, the walls had small projections at the ends and the middle of the south side, as well as the northern end of the west side. Small vaulted spaces had been created in their interior, one of them even serving as a chapel. In the middle of the east side, a large rectangular tower, housing sanitary facilities, was later added, while recent investigations unearthed the remains of similar, previously unknown towers in the middle of the north side, and the northern end of the west side of the enclosure. The main entrance to the Monastery was found in the middle of the west side (fig. 30), while evidence that indicates the existence of other, smaller secondary gates can be found on the other three sides as well. Workshops were incorporated into the lower level, together with the two existing wells. A cistern for collecting rainwater was constructed at a higher level in the southeast corner. The walls and other Justinian structures were constructed out of granite quarried from the surrounding slopes (fig. 29). At the same time, Proconnesian marble for revetments, floors, and the chancel screen of the Katholikon, brass for door cladding, lead for roofing, iron and timber for roofs, and sculpted ornamental doors etc. (fig. 31), were imported from Constantinople and the provinces. Martyrios, the spiritual father of Saint John of Sinai, was probably associated with the management of imperial funds meant for the provision of the building materials, as Nessana’s papyri attest.

The three-aisled, timber-roofed basilica of Sinai is one of the few early Christian buildings that survive intact (fig. 31). It has wide, projecting pastophoria-chapels to the east, and long, narrow side-aisles to the north and south, which lead to small, three-story towers to the west, typical of Syrian churches. The east room of the north side-aisle was originally a sacristy and perhaps library of the liturgical books while the respective bay on the south was a treasury. Two oblong rooms on the side-aisles were subdivided subsequently and converted into chapels (fig. 27).

The Holy Monastery of Sinai. Reconstruction drawing of the monastery c. 560 (PK, MMK).

The original timber roof of the basilica survives almost intact, and bears three dedicatory inscriptions, the westernmost of which is a memorial to the architect and deacon Stephanos of Aila. The other two imperial dedicatory inscriptions on the beams of the roof safely place the date of construction after the death of Theodora in the year 548, and before 560, which concurs with the current views on the time of writing the treatise On Buildings, by Procopios, the historicist of Justinian, where the church and fortress are explicitly mentioned. The monastery retains the year 557 as that of the completion of the work by tradition.

It is noteworthy that the eighteenth century Arabic inscription above the west entryway, recorded “the thirtieth year” of the reign of Justinian as the construction date of the fortress. Similar to other contemporary basilicas erected by Justinian in the Byzantine world, the new church was dedicated to the Theotokos, but at the same time, Prophet Moses was also especially revered. The team under priest Theodore that undertook the mosaic decoration of the bema apse was most probably from Constantinople, thus indicating that the decorative program commenced soon after the construction of the church. The artists were perhaps instructed on the interpretation of the multiple theological concepts by Deacon Ioannis, depicted in a small disc. Modern research has restored his identity as John of Sinai, known as John of the Ladder.

A low, rectangular narthex was soon added along the west side of the basilica. Undoubtedly, with respect to worship, the most important chapel of the Monastery is the one dedicated to the Burning Bush. From an architectural point of view, it is a rather lowly and rudimentary ground-floor addition on the axis of the east side of the Katholikon, completed around the end of the sixth century, probably during the reign of emperor Maurice (582-602) and during the time of Abbot John of Sinai (Climacus) (fig. 27).

Approaching the Holy Monastery of Sinai and its surroundings following the original path. Granite ashlar blocks were quarried from the slope on the left of the monastery, during the construction in the sixth century. Spyros Panayiotopoulos

The construction of the basilica on the summit of Mount Sinai at an altitude of 2285 meters appears to have started a little later, though still before the death of Justinian (fig. 33). This basilica replaced the initial chapel on the summit, erected by pilgrim-hermit Julian from Mesopotamia around the year 362-3, a building visited by Egeria as well. The chapel of Julian constitutes the first erected and well recorded chapel in Sinai. The Justinian basilica on the summit was three-aisled, with a five-sided apse, piers instead of columns in the nave, and also a narthex added on the west side. This basilica was most probably originally dedicated to the Holy Trinity.

About three hundred meters below, on a small plateau to the west of the Prophet Elijah chapel complex, was recently discovered a location with carved niches in the rocks and roughly hewn granite blocks. It must be here that the architectural elements of the basilica were quarried, and their haul to the top of Mount Sinai must have been a separate noteworthy technical feat.

At the same time, work must have commenced on the construction of the monumental stairway that led from the monastery to the top of Mount Sinai, through the plateau of Prophet Elijah (Fig. 20). This work, which included almost three thousand steps and two arched doorways, appears to have lasted several years. An inscription, possibly by the patron, carved on the keystone of the second doorway, which refers to Abbot Ioannis, possibly John of Sinai of the Ladder, is critical to establishing the date of the completion of the stairway. The time consuming construction of the steps must have taken place at the time when John was writing the text of the Ladder of Divine Ascent.

The Holy Monastery of Sinai. The west wall of the fortress bearing both the postern and the original entrance (today blocked). Spyros Panayiotopoulos

During the first years of the monastery, namely until about the year 641, when Alexandria was captured by the Arabs, an extensive network of hermitages and cells developed around the monastery. Most of these hermitages are now in ruins, scattered on the slopes of Mount Sinai mainly at the mountain of Moses, the mountain range Ras Safsafeh (Mount Horeb) and Saint Episteme. They are also found at Mount Serbal near Faran, and along the valleys and pathways that led through Mount Umm Shommer to the seaport of the Monastery, Raithou (El Tor), etc. Several of them survive and are functioning today, despite their antiquity, either as separate chapels, or as dependencies of the Monastery of Sinai. According to the Annales of Eutychios the patriarch of Alexandria, written in the tenth century, Justinian sent “an exarch with one hundred Roman servants together with their families” under the order to also take an equal number (of servants with their families) from Egypt, to serve as guards of the newly built monastery. Accommodations for them were provided by the construction of a complex of fortified houses to the east of the Monastery. This complex was destroyed soon after, possibly during the reign of caliph Abd al-Malik Ibn Marwan (685-705), while recent excavations by the University of Athens confirmed the accuracy of Eutychios’s account.

The adverse conditions that prevailed after the Arab conquest of the peninsula in the seventh century gradually led to the decline of monastic life, and the decrease of construction activity, as well as to the use of local, inferior building material. In subsequent centuries, though, the monastic building complex developed dynamically, and evolved into a cohesive center of habitation with a particular and singular monastic layout.

To the west of the Katholikon lies a rather large building that retains its initial tripartite layout, which probably housed the monastic refectory and kitchen (fig. 27). Its eastern part was remodeled into a mosque in the early twelfth century, while a square plan minaret was added to the north. The large, oblong building to the south-east of the Katholikon appears to have replaced a small sixth century chapel by the end of the twelfth century, a few decades before the early thirteenth century earthquake. The transverse pointed arches bear inscriptions and coats of arms by western pilgrims. It was most probably built as the new refectory of the monastery. The older Byzantine frescoes that survive in its interior date to the early thirteenth century.

Holy Monastery of Sinai, Katholikon. The royal gate of the narthex opening to the nave of the three aisled basilica. Spyros Panayiotopoulos

Small chapels continued to be built within the monastery, some of them as dedications, such as the chapel of Archangel Michael, built in 1529 by Ioakeim the Patriarch of Alexandria, and the Chapel of the Forerunner Prodromos, built in 1576 by the ruler of Vlachia, Ioannis Alexandros. To the north of the Chapel of the Forerunner a small hostel was built, to accommodate patriarchs and pilgrims from the West.

During the eighteenth century, decorative programs of the Katholikon and the chapels were carried out, and the archbishop’s quarters of the pre-Justinian tower were refurbished. In 1734, the library of Archbishop Nikiphoros Marthalēs was erected next to the Chapel of Saint John the Forerunner. After the destructive flood of 1789, the north wall was rebuilt, with the support of Napoleon Bonaparte (1801) (fig. 29).

A new, extensive decorative program that followed the current trend of classicism was carried out in the mid-nineteenth century. This program was realized partly by Sacristan Gregorios during the restoration project of the eastern wing of cells in 1875, the western wing a little later, and the construction of the belfry in 1871 on the north tower of the Katholikon. All buildings and chapels along the south side were demolished in the first half of the twentieth century, to allow space for the construction of the imposing new wing (1930-1951).

Holy Monastery of Sinai, transverse section (3-3) of the west part of the north range. The preserved in situ sixth century structures are indicated in color (PK, MMK).

The Traditional Sacristy Quarters of the Monastery

The modern sacristy, where, since 2001, selected religious treasures from the collections of the monastery are displayed, is housed only on the first floor of the building complex in the north-west corner. In the past, this area was known as the Skevofylakia, and housed storage facilities for both the Katholikon and the chapels in its ground floor, and the residence of the Sacristan possibly on the first floor.

The oldest building phase of this area dates back to the early years of the Monastery (sixth century), when a two story, granite block arcade was built along the north wall. A large part of this five-arch arcade survives in the lower section of the area, originally forming a long, two-aisled space, covered with a wooden floor (fig. 33). P. Grossmann astutely concurred that the initial function of this two-aisled space must have been to house the monastery refectory for a short period of time. This view is further supported by the existence of a propylon on the north entrance to the basilica narthex, through which the “procession” of monks used to reach the refectory (fig. 27).

Mount Sinai, Holy Summit. The chapel of the Holy Trinity (1933) behind the west wall of the narthex of the early Christian basilica (c.570). To the right the medieval mosque (eleventh/ twelfth century). PK (03/06/2006)

On the upper level, inside the area of the sacristy that survives to this day, a longitudinal and a transverse arch of the initial building survive, while their initial function remains unclear (fig. 32). The two (previously three) floors further up consisted of small rooms, and resulted from the raising of the first Justinian wall during the fifteenth century; they then underwent several consecutive repairs. They were built out of adobe bricks for the most part. Their current form appears to belong to a repair of the area and the walls carried out by Oikonomos Iakovos in 1840. In any case, several of the original small rooms survive in the west part of this area, built out of traditional stone or brick masonry, usually covered with wooden floors, or more rarely with masonry barrel-vaults.

Unfortunately, the eastern part of this area was destroyed by fire in 1971, and subsequently rebuilt using modern materials. Nevertheless, enough data on its construction history can be found in the 1979 publication by I. Dimakopoulos, and these show that the part of the sacristy that was rebuilt was similar in structure to its western part, and can thus be safely dated to the post Byzantine period.

PK–MMK